By: Dr. Daren Heyland, Critical Care Specialist, creator of Plan Well Guide, and Professor of Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston

COVID-19 has put considerable pressure on the acute care system in various countries around the world as a sizeable number of infected patients have and will require hospitalization and respiratory support. One of the most frequent and difficult decisions health care providers face is regarding the use (or non-use) of life-sustaining treatments, such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, etc. When providing care to patients, it is vital to ensure that they are prescribed care or receive treatments that align with their wishes.

While outcome data continues to evolve, it appears that for those over 80 years of age who require mechanical ventilation, the chances of surviving are less than 15% and survivors require more than three weeks of mechanical ventilation and longer hospital stays. [i] Pre-COVID-19, longitudinal follow up studies suggest that one year later, only 25% of older patients will be back to baseline, and another 25% who survive but with a much-reduced quality of life and functional status. [ii] With COVID-19, these numbers are currently unknown, but are likely much lower given the prolonged nature of the critical illness. Because many older patients would rather choose dignity-preserving treatment pathways instead of aggressive treatments against serious illness, [iii] providers are looking at ways to do a better job making sure the right treatments are applied to the right patient at the right time.

To this end, my colleagues and I surveyed over 1,200 doctors and nurses working in acute care centers across Canada to assess their main barriers to engaging older, seriously ill patients in comprehensive planning discussions. [iv] A "lack of patient/family preparedness" was identified as the main reason for this, suggesting that if we could better prepare patients (or their surrogates) for a decisional encounter, physicians would be more likely to engage and participate in goals of care discussions.

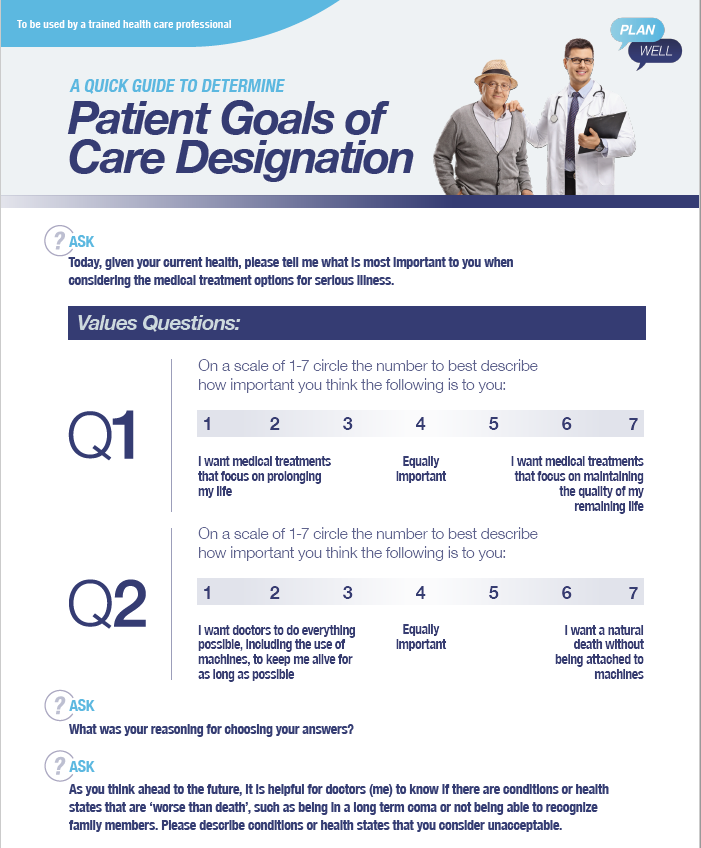

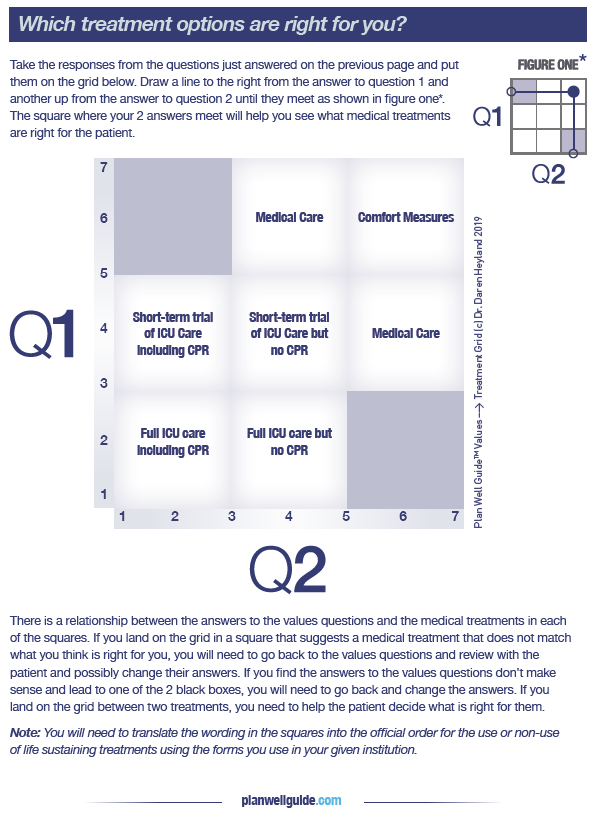

Accordingly, we developed a novel decision support tool called Plan Well Guide, to provide individuals with a free, online tool to help them understand the difference between planning for end of life care and planning for serious illness. The tool helps them clarify their authentic values using a constraining values clarification approach that helps the patient see what they are giving up to obtain what they want. (see Figures below).

It also presents a first-in-class decision aid that illustrates the risk, benefits, and possible outcomes of ICU, medical and comfort care and transparently connects those values to these possible treatment options. The goal of Plan Well Guide is NOT to have the patient make treatment decisions in advance, but rather, to prepare them for a future clinical encounter where they make decisions with a doctor in a shared decision-making model.

The results of a randomized clinical trial of Plan Well Guide demonstrate that it improves decisional quality, patient and physician satisfaction, and reduces time physicians spend on their interactions with patients compared to usual care. You can read the full article here, in CMAJ Open. If there is no time to 'prepare' the patient in advance of clinical decision-making, as often is the case, Plan Well Guide also provides a worksheet that enables clinicians to optimally elicit values and transparently links them to possible treatment preferences.

Our goal is to broadly disseminate Plan Well Guide, to engage people in advance serious illness preparations and plans to help improve clinical decision-making regarding the use (or non-use of life sustaining treatments) and to promote patient-centered care, greater satisfaction and less stress and anxiety among family and caregivers.

To learn more about or if you have any questions or comments about Plan Well Guide, please connect with Dr. Daren Heyland directly at Dkh2@queensu.ca.

References:

[i] Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et. al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet, published on line May 19, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)31189-2

[ii] Heyland DK, Stelfox HT, Garland A, Cook D, Dodek P, Kutsogiannis J, Jiang X, Turgeon AF, Day AG; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Predicting Performance Status 1 Year After Critical Illness in Patients 80 Years or Older: Development of a Multivariable Clinical Prediction Model. Crit Care Med. 2016 Sep;44(9):1718-26. PubMed PMID: 27075141.

[iii] Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States Worse Than Death Among Hospitalized Patients With Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1557–1559. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4362

[iv] You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, Lamontagne F, Ma IW, Jayaraman D, Kryworuchko J, Strachan PH, Ilan R, Nijjar AP, Neary J, Shik J, Brazil K, Patel A, Wiebe K, Albert M, Palepu A, Nouvet E, des Ordons AR, Sharma N, Abdul-Razzak A, Jiang X, Day A, Heyland DK; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):549-56. PubMed PMID: 25642797.